Written by Clara Ontal

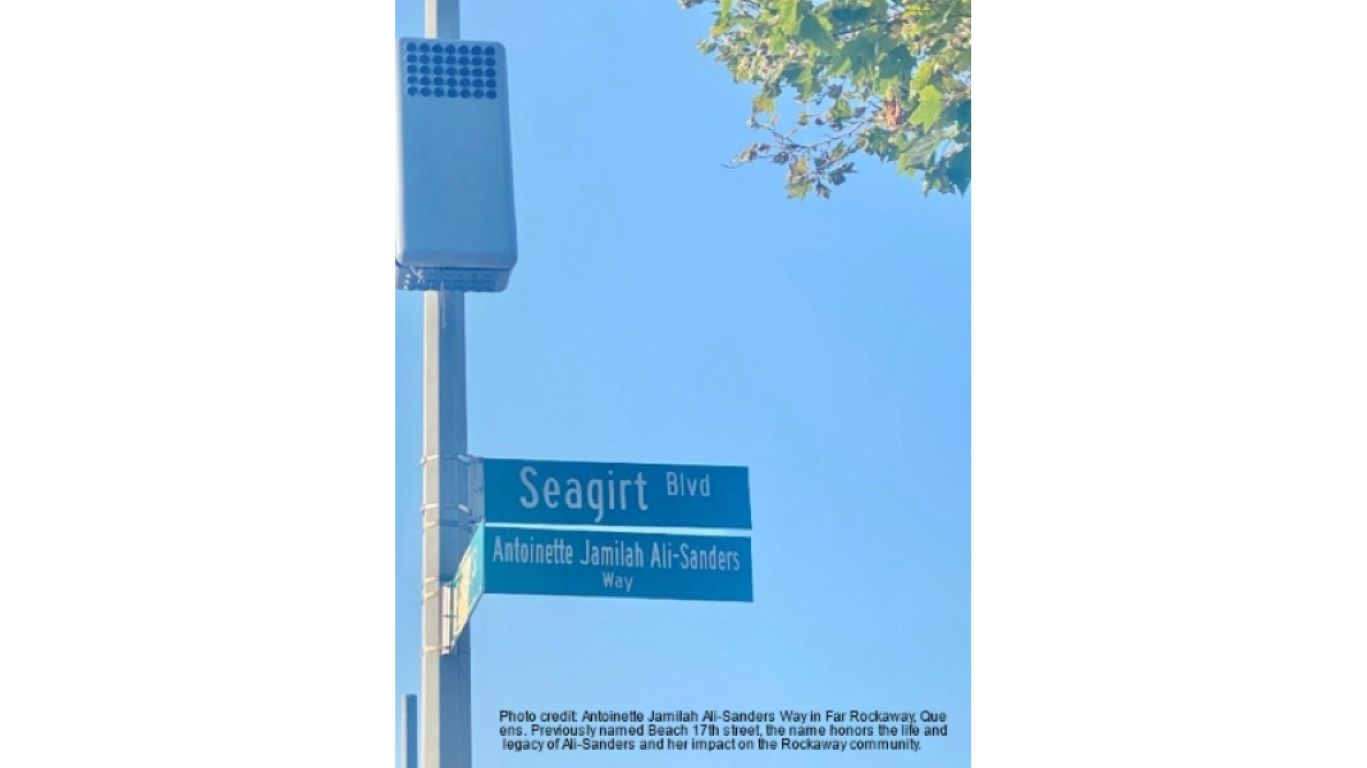

Antoinette Jamilah Ali-Sanders was an accomplished landscape architect and community activist. She broke barriers in her academic and professional career, paving the way in urban planning, landscape architecture, and education advocacy. At the intersection of Seagirt Boulevard and Beach 17th Street in Far Rockaway, Queens, a street is co-named in her honor.

Born on February 19, 1958, Ali-Sanders was the eldest of three children of Shaykh Abd'Allah Latif Ali, an activist who was instrumental in the Islamic community and Marcus Garvey movement. In an autobiographical essay written in 2015, Ali-Sanders embraces her heritage and family. She notes the significance of being a third-generation college graduate while simultaneously having dark skin. It meant her parents and grandparents had to overcome the exclusion of Black people who were “darker than a brown paper bag” from most colleges, with only colleges started by Black people, such as Tuskegee University, being the exception. Growing up in Teaneck, NJ - the first town to integrate schools - Ali-Sanders had experiences that were “sensitive and responsive to civil rights issues of the 1960s,” such as being involved in a fundraiser for Rosa Parks, which was influential in shaping her interest in social, political, and community activities. In high school, she participated in the Black Student Union, cheer squad, gymnastics team, and dance team, all while maintaining stellar grades. Thanks to her good grades and strong work ethic, she graduated high school a year early in 1975 and attended Rutgers University, where she majored in Landscape Architecture and minored in Civil Engineering. During her college years, members of the KKK broke into her car and threatened her, but Ali-Sanders persevered. In an act of solidarity, fraternity members from Kappas and Ques would walk with her to class. In 1980, Ali-Sanders became the first Black woman to earn a bachelor's degree from Rutgers’ Landscape Architecture program.

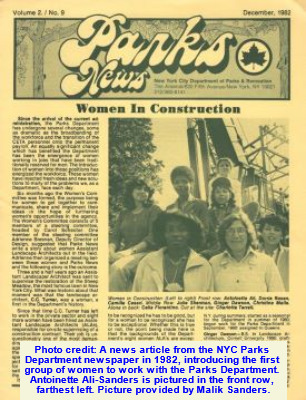

After graduation, Ali-Sanders pursued a career as a landscape designer and developer, while firmly rooted in her belief in revitalizing, not gentrifying, communities in New York and New Jersey. In 1981, Ali-Sanders began working with the New York City Parks Department. She was among the first group of women landscape designers, and she continued at the Parks Department for 35 years. During her tenure, she oversaw the construction of parks, playgrounds, and structures, and the restoration of monuments. As a union delegate, she organized against racial and gender discrimination in the workforce.

In 1982, she founded the Metro Skyway Construction Company to build affordable housing in Jersey City, NJ. Throughout the ’80s and ’90s, she built nearly 100 affordable housing units and oversaw sweat equity programs to help community members remain in their neighborhoods in Jersey City.

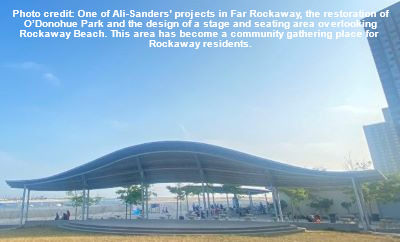

As a resident of Far Rockaway, Queens, she engaged with elected officials, community groups, and residents to raise awareness about ongoing gentrification in an effort to keep residents from being pushed out. Her aim was to revitalize Far Rockaway to serve the needs of the local community. She was inspired by Martha’s Vineyard as a “beautiful beachfront community that has a thriving Black community,” and wanted to apply this model to Far Rockaway. She achieved this vision through her restoration of O’Donohue Park. Her design of a stage and seating area overlooking Rockaway Beach allows residents to gather for community events and enjoy a meal from the waterfront restaurant, DredSurfer.

Ali-Sanders also advocated for various causes related to civic empowerment and educational opportunities, and was actively involved in city politics. In the 1990s, she began volunteering with the All Stars Project, working on the Committee for Independent Action - a community organizing initiative that trained people to advocate on behalf of the city’s poor. In 1994, she was involved with the New York State Black Political Convention and was a member of the National Action Network. She attended legislative and policy conferences in Washington, DC, where she advocated on behalf of the Black community. She also met with national leaders, learning firsthand about upcoming legislation, which she would then relay back to the network for further action.

During this time, Ali-Sanders played an active role in advocating for improvements in Black education. She joined the Association of Black Educators of New York (ABENY) and hosted her own cable access show, “Jamilah Ali Community Affairs Program,” an advocacy platform for advancing Black education and wellness in the community. (Spencer, Christian. “A Street for Jamilah.” The Wave, 03 October 2019, paragraph 14.)

Compassion was an impetus for her community activism and was just as present in her relationships with family and friends. Safiah Ali-Jenkins, Ali-Sanders’ younger sister, fondly recalls, “As my oldest sister, she always had time for me and would allow me to tag along with her and her friends. My fondest memories were when she went to college when I was only seven, and I would spend weekends with her in her dorm. She would take me to basketball games, campus functions, and parties. Those were some of the best times of my childhood.” Ali-Sanders’ stepdaughter Nzinga Cerrice Dawson, who refers to Ali-Sanders as Jamilah, said “Jamilah taught me so much about life and parenthood. Her example influenced many of the choices that I made when I had my children (i.e. only giving them homemade baby food and only having Black characters in their books/toys). The way she loved me became the blueprint for when I became a stepmother myself.”

Malik Sanders, Ali-Sanders' son, continues to be inspired by the way his mother “fought for her family and community, no matter what the odds against her.” He recounts how she had battles of her own and still found time to give to others, teaching him “to remember that everyone we meet may be facing personal battles, and we should try to extend the same grace we would like to have extended our way.”

To this day, she is remembered fondly for her kind nature and compassion towards her community. At her favorite local eatery, the DredSurfer restaurant on Rockaway beach, workers Mercedes and Charles remember her as a dear kind friend who enjoyed good conversation along with her meals, while overlooking the water. Mercedes remembers how Ali-Sanders and Charles’ young niece, Justice, would play together on the beach. When Justice was informed of Ali-Sanders’ passing, she cried a lot at the loss of a friend. Mercedes said Ali-Sanders was not one to boast of her many accomplishments. Mercedes found out only after her passing that the landscape surrounding the DredSurfer was designed by Ali-Sanders.

Following her passing in 2019, Queens Borough President Donovan Richards co-named Beach 17th Street after Ali-Sanders to honor her achievements and contributions to the community. At the time, her son, Malik, was working on land use at the Borough President's Office and launching an environmental initiative with his colleague, Katherine Brezler. He describes the initiative as a continuation of her legacy: “My mom is definitely looking down smiling…That is a program after her own heart.”

Thank you to Malik Sanders and the family of Antoinette Jamilah Ali-Sanders for their contributions to this article.