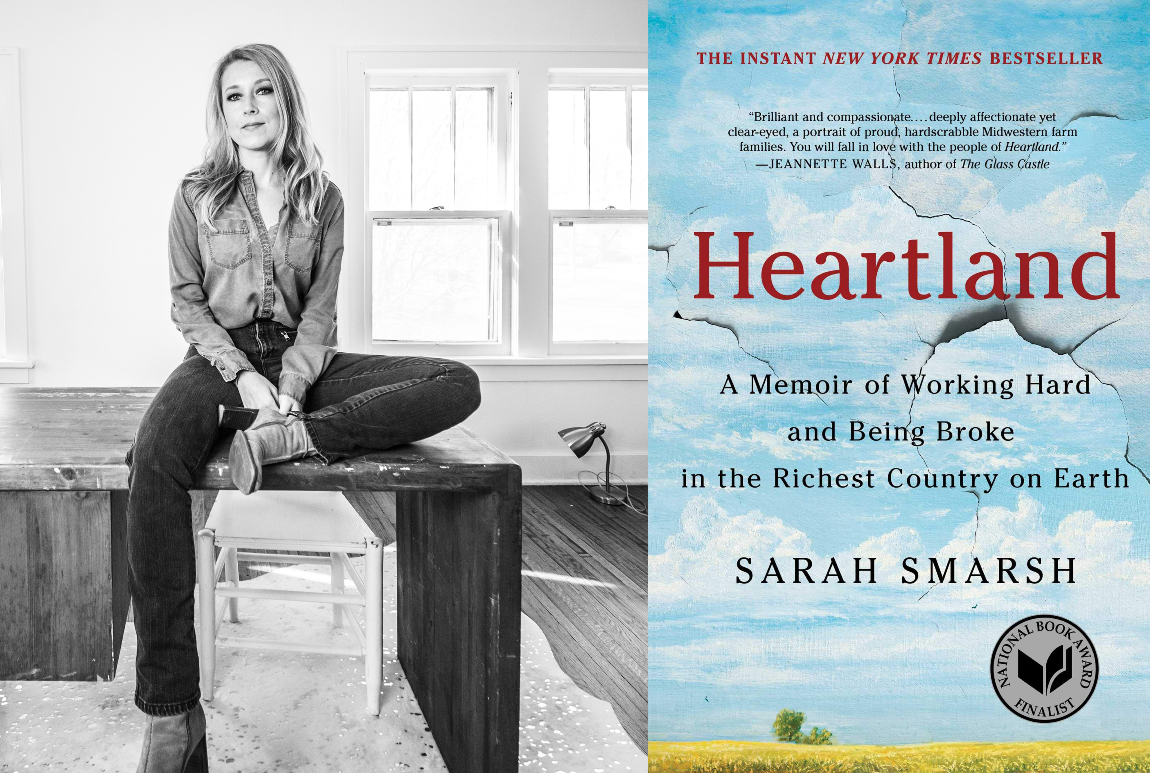

Sarah Smarsh, the first-time author of Heartland: A Memoir of Working Hard and Being Broke in the Richest Country on Earth, began her book in 2002 while a senior at the University of Kansas, researching her family’s chaotic history.

Sixteen years later, it was a finalist for the National Book Award. “I’d never won an award for my professional writing, not even a local reporting award. So I don’t write or work with any real awareness of the awards realm. I didn’t know the finalist longlist was being announced that day. So the calls and emails were quite shocking—and thrilling! Then, making the short list and attending the red-carpet awards ceremony in New York was beyond a dream come true in that I’d never even dreamed it,” she says. Nowadays, Smarsh is doing public speaking and media appearances on the themes of her book: socioeconomic inequality, health, poverty, rural issues, and civic identity.

Smarsh considers herself a reader even more than a writer, noting that “language is my professional tool, so reading is to me as sharpening a saw is to my carpenter dad. I live in a constant stream of books, magazines, print newspapers, digital news. But beyond vocation, reading is my life and my joy, perhaps more so even than writing, and that’s been true since my earliest memories.”

Smarsh grew up with school libraries playing a larger role in her life than town libraries, which were at a distance. “For much of my childhood, I lived on a farm that was ten miles away from the closest small-town library. Public school libraries and librarians, whom I encountered daily during the school year, were therefore a much larger presence in my life,” she says, “But I have a vivid memory of spending a week with a cousin in a small Kansas town—she lived on a brick street rather than a dirt road!—and running with glee toward the bookmobile their public library sent around town.”

In her life now, “as a journalist and researcher I often access public records through libraries and state historical societies. As a lover of books, I have a library card in my wallet for about five different cities.”

The books that inspired her as a teenager include Angela’s Ashes by Frank McCourt and I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou, because, as she explains, they “showed me it was okay to write with the rhythm of the language spoken by your family and community rather than a more formal, ‘educated’ English. This is particularly important for memoirs that are bearing witness to social injustice such as poverty or racism. I always knew that I wanted to validate the dialect and colloquial language of my home.”

In her memoir, Smarsh tells her story to an imaginary daughter called August, an internal dialogue she says “was a true, lived experience for me for many years. It helped me navigate the difficult crossroads of being both poor and female. Sharing such an intimate thing with readers was an effort to put economic hardship in the context of lived, human experience rather than abstract terms.”

The book includes narrative shifts in tone and style, which Smarsh explains “reflect shifts in my daily use of language, a sort of linguistic and socioeconomic code switching between my rural dialect and the academic or journalistic language I learned through school and profession. Yes, I speak ‘country’ every day with family and friends in Kansas, where I still live.”

Smarsh is excited when she meets people on her book tour who are new to book events or who are buying the book for someone who doesn’t usually read books: “People who have lived the story of Heartland—farmers, fast-food workers, plumbers, teen mothers, waitresses, and so on—are not marketed to, as a book-buying demographic. There are many reasons for that, from culture to lack of purchasing power. But maybe even more than that, if you never see your place and your story validated in narrative, you’re less likely to be a book person...To feel recognized and understood in the pages of a story is an experience that all people deserve.”

Smarsh suggests that if you’re not engaged with reading, you try reading different material, but she also believes love of reading comes from being surrounded by books. “If reading doesn’t light you up, more than likely you haven’t yet connected with the sort of book or poem or magazine that speaks to you. And you probably, like myself, don’t come from a family or culture or class where books are a common feature of daily life.”

She encourages everyone to acknowledge their tremendous value as human beings. “Whoever told you that you aren’t worth much—as a worker, a student, a son or daughter—don’t believe them. That piece of you, deep down, that knows your own immense worth: That’s the truth. Believe that, and let your decisions flow from there.”