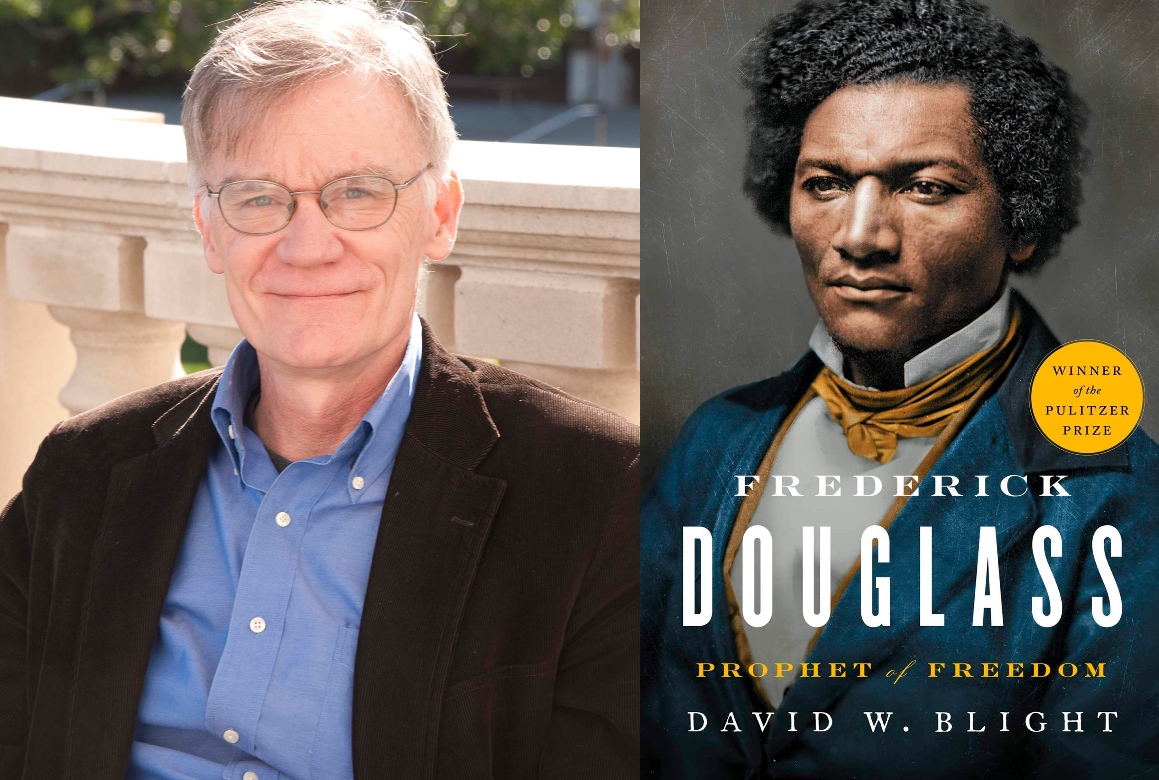

Frederick Douglass was one of the greatest abolitionists, known for his powerful oratory. David W. Blight, author of a new biography of Douglass and winner of the Pulitzer Prize, will visit Flushing Library on Saturday, November 16 at 2pm. Register for his talk at davidwblight.eventbrite.com. His book, Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom, is available now at Queens Public Library. This conversation is courtesy of Simon & Schuster, the book’s publisher.

Q. Can you discuss the tension the aging Douglass experienced as he made the transition from radical outsider to political insider and symbolic figure of great fame?

Few radical reformers in history live to see their causes triumph, and then also live long enough to become a political insider within the government or a system they had fought to overthrow, destroy, and reinvent. Nelson Mandela comes to mind. Vaclav Havel and many other Eastern European leaders after the fall of the Soviet Union and the Berlin Wall also come to mind. Some of America’s major Civil Rights leaders who later became major office holders also are good examples. Douglass is the greatest example of this phenomenon in the 19th century. In his case this meant becoming a loyal advocate of the Republican Party for thirty years as it decisively changed from the party of emancipation and the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments to the party of big business and the retreat from the egalitarian transformations of Reconstruction.

Douglass became an office holder (by appointment, not election), he became often a symbol as much as an actual political leader. Douglass always had to live up to expectations of performing as the black leader, the voice of the freedpeople, the former slave who had to prove the capacities of black people. But above all Douglass also became in the final thirty years of his life, 1865-1895, a patriarch of a huge extended family of three sons, one daughter, and twenty-one grandchildren. Along with his two wives over time, these kinfolk all became to one degree or another financially dependent on Douglass. Living in Washington, his family emerged as a kind of black first family in the District of Columbia press. Douglass, therefore, lived with an acute problem of “fame,” in all its positive and negative aspects.

Q. How would you characterize Douglass’s legacy today? What lessons could we all—political leaders, cultural leaders, and active citizens—take from his life and work?

Douglass delivers many legacies to us today in the 21st century, both from the trajectory of his life and from his ideas and writings. He is first one of the best examples ever of a person who led by language, a genius with words whose oratory and writing provide the primary reasons we know him. Second, Douglass delivered over and over a critique of America as a slave society that had to be dismembered and destroyed before being recreated around the idea of human equality. Third, Douglass’s writings, especially in the autobiographies, constitute the most compelling descriptions and analysis of the nature and meaning of American slavery crafted by any American. Fourth, on a personal level, for anyone who has ever experienced despair, captivity, oppression in many forms, displacement, isolation of the soul, or legal and political denial, Douglass’s story, and his writings, offer a deep well of hope and inspiration.

Fifth, Douglass might have given up on the cause of abolition, of emancipation, of U.S. victory in the Civil War, or of the endurance of the triumphs for black rights in Reconstruction. But he never truly gave up. That alone gives his life and thought lasting use and significance. Sixth, Douglass was a great editor, writer, speaker. He was an organizer, a creator of and believer in social protest movements. All who seek social and political change or transformation do well to examine Douglass’s example. Seventh, Douglass remains a classic model of political pragmatism grown out of radicalism. His story shows us over and again that all revolutions will lead to counter-revolutions. A true reformer has to keep a long view of history, and try to fashion the most effective and not always the most radical method of change.

Eighth, Douglass not only lived a heroic life in his escape from slavery and the remaking of himself in freedom; he became a major thinker—about the nature of history, about the natural rights tradition, about political and constitutional philosophy, about the elements of morality in human nature. Ninth, Douglass has a great deal to tell us eternally about what it means to be an American, and about how the issue and history of race stands at the center of that question. And tenth and finally, but not least, Douglass’s world view, sense of history, and his gripping talent for storytelling rested deeply in his reading and use of the Bible, especially the Old Testament. Just why Americans in the nineteenth century were so steeped in Biblical story and metaphor is beautifully and powerfully on display in Douglass life and work.

David W. Blight is the Sterling Professor of History and Director of the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition at Yale University. He is the author or editor of a dozen books, including Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom; American Oracle: The Civil War in the Civil Rights Era; and Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory; and annotated editions of Douglass’s first two autobiographies. He has worked on Douglass much of his professional life and been awarded the Pulitzer Prize for History, the Bancroft Prize, the Abraham Lincoln Prize, and the Frederick Douglass Prize, among others.

Photo of David W. Blight courtesy of Huntington Library, San Marino, California.