In honor of African-American History Month, we're paying tribute to a special selection of notable African-American writers.

Check this blog post every week in February for updates!

February 3: Langston Hughes

February 7: Naomi Jackson

February 10: Darryl "DMC" McDaniels

February 14: Phillis Wheatley

February 17: Colson Whitehead

February 21: Lorraine Hansberry

February 24: MK Asante

February 28: James Baldwin

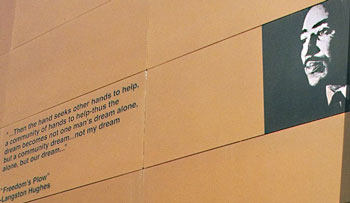

Langston Hughes was a poet, novelist, and political activist, best known as a primary contributor to, and leader of, the Harlem Renaissance—an explosion of influential African-American art, music, and culture in New York City from about 1918 to the mid-1930s. His signature poem, “The Negro Speaks of Rivers,” was written when he was seventeen years old and published in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People’s official magazine, The Crisis, in 1921. It was included in his first poetry collection, The Weary Blues, in 1926.

Langston Hughes was a poet, novelist, and political activist, best known as a primary contributor to, and leader of, the Harlem Renaissance—an explosion of influential African-American art, music, and culture in New York City from about 1918 to the mid-1930s. His signature poem, “The Negro Speaks of Rivers,” was written when he was seventeen years old and published in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People’s official magazine, The Crisis, in 1921. It was included in his first poetry collection, The Weary Blues, in 1926.

Hughes was born on February 1, 1902, in Joplin, Missouri, and raised by his grandmother until the age of thirteen. His father had fled racism in America by going to Cuba and Mexico, and his mother had traveled seeking work. While still in elementary school, he was elected Class Poet. He was later reunited with his mother and stepfather and attended high school in Cleveland, Ohio. While he did maintain a relationship with his father, it was always strained, partially due to his aspirations of being a writer. Working a number of odd jobs, he would eventually travel abroad as a ship’s crewman. He spent time in England with the black expatriate community that had surged there after World War I. After returning to the States, he made the acquaintance of poet Vachel Lindsay, and later was classmates with Thurgood Marshall at Lincoln University, a historically black university in Chester County, Pennsylvania. Hughes earned his B.A. in 1929. He was extremely political, which was evident in his prolific writing. He protested against Jim Crow segregation laws and traveled the world in creative endeavors with radical left activists. Hughes was accused of Communism by the members of the political right, and eventually, with much criticism from his fanbase, distanced himself from politics in his writing as well as his public life. Though never confirmed while he was alive, a number of Hughes’s works have been interpreted as odes to male love interests. He has remained an inspirational figure in black and LGBTQ communities alike.

Langston Hughes published 15 collections of poetry during his career, including Montage of a Dream Deferred (1951), a suite of poems meant to be read as a single work. He also published 11 books of fiction, seven books of non-fiction, 12 major plays—including Mule Bone (1931) with Zora Neale Hurston—and eight children’s books. He earned a number of accolades in his life, including a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1935, the Spingarn Medal from the NAACP in 1960, and honorary doctorates from Howard University and Western Reserve University. Following his death, many memorials have been named in his honor: the first Langston Hughes Medal was awarded by the City College of New York in 1978; the Langston Hughes Middle School opened in Reston, Virginia, in 1979; Langston Hughes High School opened in Fairburn, Georgia in 2009; and his home on East 127th Street in Harlem received landmark status from the City of New York in 1981. We, of course, can’t leave out the Langston Hughes Community Library and Cultural Center in Corona, Queens, which opened in 1969, and gained full status in the Queens Library system in 1987. Image credit: Langston Hughes photographed by Carl Van Vechten, 1936.

Naomi Jackson is a New York-based author whose debut novel, The Star Side of Bird Hill, has launched her into literary stardom. Since its release in 2015, this poetic prose about two young girls who are forced to relocate from Brooklyn to Barbados was named an Honor Book for Fiction by the Black Caucus of the American Library Association. It was nominated for an NAACP Image Award and the Hurston/Wright Legacy Award. The Star Side of Bird Hill was also selected for the Gracie Book Club, the project launched by First Lady of New York Chirlane McCray in 2016.

Naomi Jackson is a New York-based author whose debut novel, The Star Side of Bird Hill, has launched her into literary stardom. Since its release in 2015, this poetic prose about two young girls who are forced to relocate from Brooklyn to Barbados was named an Honor Book for Fiction by the Black Caucus of the American Library Association. It was nominated for an NAACP Image Award and the Hurston/Wright Legacy Award. The Star Side of Bird Hill was also selected for the Gracie Book Club, the project launched by First Lady of New York Chirlane McCray in 2016.

Jackson was born and raised in Flatbush, Brooklyn by her West Indian parents. She attended Williams College in Massachusetts for her undergraduate degree and then studied fiction at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop in 2011. She attended the University of Cape Town on a Fulbright Scholarship and received an M.A. in Creative Writing. She was the 2013-2014 resident at The Kelly Writers House at the University of Pennsylvania, and also had residencies at Hedgebrook in Washington and the Camargo Foundation in Cassis, France. She also, of course, spent considerable time traveling in the Caribbean and connecting with her familial roots there. Jackson has taught writing at her alma mater, the University of Iowa, as well as Oberlin College, the University of Pennsylvania, and the City College of New York. She is currently the Visiting Writer at Amherst College.

Before The Star Side of Bird Hill, Jackson was published in many literary journals, popular magazines, and websites, including Word Without Borders, Buzzfeed, Bloom Literary Journal, espnW.com, and Elle Magazine, just to name a few. She continues to publish essays and short stories, has been reviewed by the likes of The New York Times, Entertainment Weekly, and NPR, and was named a “Writer to Watch” in Fall 2015 by Publishers Weekly. We certainly will be watching as her career continues to flourish! Image credit: Photo of Naomi Jackson by Lola Flash, courtesy of naomi-jackson.com.

Darryl "DMC" McDaniels helped change the way the mainstream saw hip hop by the time Run-DMC hit number six on the Billboard 200 with their third album Raising Hell in 1986. McDaniels co-wrote the lyrics on much of the album, most notably the two original singles “My Adidas” and “It’s Tricky.” The break-out hit, however, was a cover with a twist—a rap-rock version of Aerosmith’s “Walk This Way” with guest performances by Steven Tyler and Joe Perry. The album was number one on the Billboard R&B/Hip Hop charts and marked the beginning of hip hop’s evolution into popular music. The album continues to influence artists of every genre, and is considered by Time, Rolling Stone, and Slant Magazine to be one of the greatest albums of all time.

Darryl "DMC" McDaniels helped change the way the mainstream saw hip hop by the time Run-DMC hit number six on the Billboard 200 with their third album Raising Hell in 1986. McDaniels co-wrote the lyrics on much of the album, most notably the two original singles “My Adidas” and “It’s Tricky.” The break-out hit, however, was a cover with a twist—a rap-rock version of Aerosmith’s “Walk This Way” with guest performances by Steven Tyler and Joe Perry. The album was number one on the Billboard R&B/Hip Hop charts and marked the beginning of hip hop’s evolution into popular music. The album continues to influence artists of every genre, and is considered by Time, Rolling Stone, and Slant Magazine to be one of the greatest albums of all time.

Darryl Matthews McDaniels was born on May 31, 1964 in Harlem, New York, but was surrendered to the New York Foundling home by his mother. He was eventually adopted, and raised in Hollis, Queens. At the age of 14, he began teaching himself how to DJ on equipment given to him by his older brother. He soon teamed up with friends Joseph "Run" Simmons and Jason “Jam Master Jay” Mizell. McDaniels was encouraged to rap, rather than DJ. He used the moniker DMcD—how he signed his work in school—shortened later to just “DMC.” In 1984, Run-DMC released their self-titled debut to much positive feedback from the music community. DMC had already been abusing alcohol for some time by this point, using it to overcome stage fright since age 15.

By the release of Raising Hell, creative differences had emerged within the group, and tensions grew. In 1991, he was hospitalized with acute pancreatitis and made the decision to quit drinking cold turkey, though he would experience backslide. He met his wife Zuri Alston in 1992, and they had their son Darryl “D’Son” McDaniels, Jr. in 1994. In the late '90s, DMC suffered from spasmodic dysphonia, a condition that robbed him of his iconic rap voice. It was during this same time that he first learned of his adoption. This was the tail end of a depression spiral that had included suicidal thoughts for well over a decade. He credits an unexpected source for finding hope—the music of Sarah McLachlan. In 2004, he completed inpatient treatment for alcoholism and has been sober ever since.

DMC released a solo album, Checks Thugs and Rock n Roll, in 2006. In 2014, he founded his own independent comic book imprint, Darryl Makes Comics. The first book he released was DMC, featuring a superhero designed after himself who thwarts heroes, as well as villains, who have let their powers get out of control. His memoir Ten Ways Not to Commit Suicide was published in 2016 by Harper Collins. We were honored when DMC visited Queens Library in December 2015 and spoke with our Hip Hop Coordinator Ralph McDaniels about his life, his career, and the past and future of hip hop culture. Image credit: Photo of DMC by MFidel Photography, part of the February 2017 “Queens Hip Hop Pioneers” photo exhibit at Central Library in Jamaica.

Phillis Wheatley was the first published African-American female poet, with an extraordinary gift for languages and great capacity for learning. Poems On Various Subjects, Religious and Moral was the one collected volume of her work published in her lifetime, when she was 20 years old. The book’s publishing was paid for, in part, by patrons of English nobility and the Wheatley family, by whom she had been purchased as a slave.

Phillis Wheatley was the first published African-American female poet, with an extraordinary gift for languages and great capacity for learning. Poems On Various Subjects, Religious and Moral was the one collected volume of her work published in her lifetime, when she was 20 years old. The book’s publishing was paid for, in part, by patrons of English nobility and the Wheatley family, by whom she had been purchased as a slave.

Her birthdate is presumed to be in 1753 in West Africa, but exact information is sparse. She was kidnapped and sold at the age of seven or eight and brought to Massachusetts on a ship called The Phillis, which is where she got her first name. A wealthy Boston merchant by the name of John Wheatley purchased her as a slave for his wife, Susana. The family was considered somewhat progressive in their time, and young Phillis received an unprecedented education, not only for a slave, but for any girl. By age 12 she could read in English, Greek, and Latin, and by age 13 was writing poetry. The family enjoyed showing off her skills, and rather than have her do physical chores, escorted her on audiences with the likes of Selina Hastings, the Countess of Huntingdon, whose patronage helped in publishing her first volume of poems in London. This was after failing to publish the volume in America, and having to prove the work was hers in court. The general perception at the time was that Africans could not write, let alone write poetry.

Phillis Wheatley would also later meet George Washington after writing an ode to him, which was later republished in the Pennsylvania Gazette by Thomas Paine. She also kept correspondence with Reverend Samson Occom and the British philanthropist John Thornton. As per John Wheatley’s will, Phillis was freed upon his death in 1778. She had lost her patronage after gaining her freedom. She married a freedman named John Peters, but the two had many financial and emotional struggles. They lived in poverty and suffered through the death of two infants, and her husband was eventually incarcerated in debtors’ prison. Phillis wrote a second volume of poetry, but was unable to have it published as a book, though selected poems would be run in magazines and pamphlets. In 1838, the third edition of Margaretta Matilda Odell's Memoir and Poems of Phillis Wheatley, A Native African and a Slave collected Wheatley's poems along with those of enslaved North Carolina poet George Moses Horton, who was the first African-American poet to be published in the southern United States.

Phillis Wheatley’s work is widely considered essential in black literature. Her first published volume made her the most famous black woman in the world; French philosopher Voltaire was said to be a fan. While recognized for her skill during her life, her subtle subversion and the allusions and double meanings of her works have been studied and analyzed long after her death. Robert Morris University named the new building for their School of Communications and Information Sciences after her in 2012, and Wheatley Hall at UMass Boston is named for her as well. She is featured both in the Boston Women's Memorial and on the Boston Women's Heritage Trail. In 2002, professor and scholar Molefi Kete Asante named Phillis Wheatley one of the 100 Greatest African Americans.

Colson Whitehead is a New York-based author whose most acclaimed book to date is his sixth novel, The Underground Railroad, published in 2016. The story follows two slaves in their bid for freedom—only the Underground Railroad in this world is quite literal. A subway system takes them on a journey through time and shows them the beginnings of bondage, to the struggles of the modern day. This unique novel was given a National Book Award for Fiction, and hit the height of popularity when it was selected for Oprah’s Book Club in August 2016. It was also part of President Barack Obama’s personal summer reading list. In January 2017, the American Library Association awarded The Underground Railroad the Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence. It was also a New York Times bestseller and was selected as one of their Ten Best Books of 2016.

Colson Whitehead is a New York-based author whose most acclaimed book to date is his sixth novel, The Underground Railroad, published in 2016. The story follows two slaves in their bid for freedom—only the Underground Railroad in this world is quite literal. A subway system takes them on a journey through time and shows them the beginnings of bondage, to the struggles of the modern day. This unique novel was given a National Book Award for Fiction, and hit the height of popularity when it was selected for Oprah’s Book Club in August 2016. It was also part of President Barack Obama’s personal summer reading list. In January 2017, the American Library Association awarded The Underground Railroad the Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence. It was also a New York Times bestseller and was selected as one of their Ten Best Books of 2016.

Whitehead was born on November 6, 1969 in Brooklyn, and grew up in Manhattan. He attended Harvard University, though he was not accepted into their creative writing program during his education. Very soon after his graduation in 1991, he began writing for The Village Voice as an editorial assistant and a TV, book, and music critic. He started writing his first novels during this time. In 2002, he was granted a MacArthur Fellowship, which is colloquially known as “The Genius Grant.” Whitehead has also written for The New York Times, Salon, Vibe, Spin, and Newsday. He’s taught at top schools in and around New York City: New York University, Columbia University, Brooklyn College, Hunter College, and Princeton University. He has also taught at the University of Houston and Wesleyan University, and had writing residencies at Vassar College, the University of Richmond, and the University of Wyoming.

Whitehead has to date written eight books—six novels, a collection of essays about New York City (The Colossus of New York, a New York Times Notable Book of the Year), and a memoir about participating in the 2011 World Series of Poker (The Noble Hustle). His first novel, The Intuitionist (1999), was a finalist for the PEN/Hemingway Award and won the Quality Paperback Book Club’s New Voices Award. John Henry Days (2001) received the Young Lions Fiction Award and the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award, and was a Pulitzer Prize finalist. Apex Hides the Hurt (2006) won the PEN Oakland/Josephine Miles Literary Award, and Sag Harbor (2009) was a finalist for the PEN/Faulkner Award and the Hurston/Wright Legacy Award. Whitehead is a 2000 Whiting Award winner and has also received the Cullman Center for Scholars and Writers Fellowship (2007), the Dos Passos Prize (2012), and a Guggenheim Fellowship (2013). Image credit: Colson Whitehead at the 2009 Texas Book Festival in Austin, via Wikimedia, copyright Larry D. Moore.

Lorraine Hansberry was the first black woman to write a play performed on Broadway. Her most famous work is A Raisin in the Sun, the name of which is a reference to the Langston Hughes poem “Harlem (A Dream Deferred).” The play, which debuted in 1959, chronicles an African-American family living in a run-down home in the south side of Chicago that attempts to improve their lives after receiving a substantial life insurance payout after a relative's death. The play deals with racial injustice, integration, poverty and economic mobility, ethnic pride, and the pursuit of the American dream. Much of the play echoes real-life events surrounding Hansberry v. Lee (1940), a Fair Housing Act lawsuit involving Hansberry’s family.

Lorraine Hansberry was the first black woman to write a play performed on Broadway. Her most famous work is A Raisin in the Sun, the name of which is a reference to the Langston Hughes poem “Harlem (A Dream Deferred).” The play, which debuted in 1959, chronicles an African-American family living in a run-down home in the south side of Chicago that attempts to improve their lives after receiving a substantial life insurance payout after a relative's death. The play deals with racial injustice, integration, poverty and economic mobility, ethnic pride, and the pursuit of the American dream. Much of the play echoes real-life events surrounding Hansberry v. Lee (1940), a Fair Housing Act lawsuit involving Hansberry’s family.

The play’s predominantly black cast made it a difficult sell for funding at the time, but it opened to very positive reviews and continues to be considered a pivotal production in American theater. The original cast starred Sidney Poitier and Claudia McNeil, who were nominated as Best Actor and Actress at the Tony Awards in 1960. The production was also nominated for Best Play and Best Direction. A Raisin in the Sun saw two Broadway revivals: one in 2004, starring Sean Combs, Audra McDonald, and Phylicia Rashad (who also reprised their roles for a 2008 TV movie); and one in 2014, starring Denzel Washington and Sophie Okonedo, that won three Tony Awards. It was also a West End production in 1959, and was performed at the Royal Exchange Theatre in Manchester in 2010. An acclaimed film version was made in 1961, for which Hansberry wrote the screenplay, starring the original Broadway cast. A musical version of the play, Raisin, ran for two years on Broadway beginning in 1973 (with its book written by Hansberry’s ex-husband) and won the Tony Award for Best Musical.

Lorraine Vivian Hansberry was born in Chicago on May 19, 1930, the youngest of four children. Her family achieved a certain kind of fame after buying a home in a mostly white neighborhood, which collectively made legal attempts to force them out in the case Hansberry vs. Lee. The case made its way to the Supreme Court. The Hansberrys were a well-respected family and were friendly with renowned intellectuals such as W.E.B. Du Bois and Paul Robeson. Hansberry graduated from Englewood High School in 1948. She attended the University of Wisconsin–Madison, where she was incredibly politically active, and briefly studied painting at the University of Guadalajara, Mexico in 1949. In 1951 she moved to Harlem, studied writing at the New School, and continued her activism work, focusing primarily on underprivileged families fighting evictions. That same year, she joined the staff at the Freedom newspaper, where she continued professional relationships with Robeson (founder of the newspaper) and Du Bois. Most of her work focused on American civil rights struggles and global anti-colonialism. In 1953, she married Robert Nemiroff, a prominent publisher and songwriter, though it is believed that Hansberry was a closeted lesbian. Nemiroff’s success allowed Hansberry to write full-time. The two did separate in 1957, and divorced in 1964, but continued to work together throughout the rest of Hansberry’s life. A lifelong smoker, Hansberry died of pancreatic cancer at the age of 34. Paul Robeson was one of the eulogizers at her funeral, and messages from James Baldwin and the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. were also recited.

Only one more of Hansberry’s plays was performed onstage during her lifetime. The Sign in Sidney Brustein's Window premiered on Broadway in 1964, but was met with mixed reviews, and closed nearly three months after its opening. Hansberry considered Les Blancs to be her most important play. It was finished by Nemiroff after her death and debuted on Broadway in 1970, to heavy criticism. Les Blancs and two of Hansberry’s other plays were compiled in a book edited by Nemiroff and first published in 1972. Her autobiography, To Be Young, Gifted and Black, was also completed posthumously, and published in 1969. Nina Simone released a song in tribute to Hansberry under the same title that same year. Two elementary schools in New York City are named for Hansberry, in the Bronx and in St. Albans, Queens. Pennsylvania’s Lincoln University has a first-year female dorm named after her, and she has also been honored in San Francisco with the Lorraine Hansberry Theatre. In 1999, she was added to the Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame, and to the American Theatre Hall of Fame in 2013. Image credit: Fair Use, via Wikimedia.

MK Asante is an author, hip hop artist, filmmaker, and professor. He reached notoriety with his memoir Buck (2013), the story of his life as a teenager on the tough streets of his Philadelphia neighborhood, as his family fell apart. Readers were inspired by his story of self-discovery through self-education, as he found his voice through writing at the age of sixteen. The book had immediate positive critical reception, with stellar reviews from NPR, the Los Angeles Times, the San Francisco Book Review, and even poet Maya Angelou, who called the book “a story of surviving and thriving with passion, compassion, wit, and style.” Buck was selected for the Barnes & Noble Discover Great New Writers list and was an LA Times Summer pick. It won numerous awards, including Best New Book of 2013 from Baltimore Magazine, and the 2014 In the Margins Book Award.

MK Asante is an author, hip hop artist, filmmaker, and professor. He reached notoriety with his memoir Buck (2013), the story of his life as a teenager on the tough streets of his Philadelphia neighborhood, as his family fell apart. Readers were inspired by his story of self-discovery through self-education, as he found his voice through writing at the age of sixteen. The book had immediate positive critical reception, with stellar reviews from NPR, the Los Angeles Times, the San Francisco Book Review, and even poet Maya Angelou, who called the book “a story of surviving and thriving with passion, compassion, wit, and style.” Buck was selected for the Barnes & Noble Discover Great New Writers list and was an LA Times Summer pick. It won numerous awards, including Best New Book of 2013 from Baltimore Magazine, and the 2014 In the Margins Book Award.

Molefi Kete Asante, Jr. was born in Harare, Zimbabwe in 1982. His parents are American—his father is African-American scholar Molefi Kete Asante, and his mother is choreographer and professor Kariamu Welsh. He and his older brother were raised in north Philadelphia. Asante had a difficult time growing up in a neighborhood in decay—his older brother was arrested, his father was often absent, and his mother in poor health. He struggled with drugs and gang affiliation. Due largely to all the turmoil in his life, he had problems in school. He eventually enrolled in an alternative high school where he discovered his love of writing. He went on to earn his bachelor’s degree at Lafayette College, and his MFA from the UCLA School of Theater, Film, and Television.

Asante published three books before the release of his memoir: two collections of poetry, Like Water Running Off My Back (2002) and Beautiful. And Ugly Too (2005), as well as a non-fiction book, It's Bigger Than Hip Hop (2008), about musical subculture and politics. After Buck’s critical reception, Asante received a Sundance Institute Feature Film Program grant to adapt it into a movie, which is currently in development. He wrote and produced the independent documentary 500 Years Later (2005), which won Best Film at the 2005 Berlin Black Film Festival and the 2007 UNESCO/Zanzibar International Film Festival "Breaking the Chains" Award. He also directed the documentary The Black Candle (2008), which was written and narrated by Maya Angelou. His debut album is a hip hop companion to his memoir called Buck: The Original Book Soundtrack (2015). Asante has given lectures and performances in over 25 countries and at many prestigious institutions, including Yale University, Vassar College, Harvard University, and the British Library. He is currently an Associate Professor of Creative Writing and Film at Morgan State University in Baltimore, Maryland, having received tenure at twenty-six.

The youngest person on our list, we will surely have much more to read and hear from him in the future! Image credit: Throwacoup via Wikipedia Commons.

James Baldwin was an essayist, novelist, playwright, poet, and social critic. His most famous work, amongst many, is Go Tell It On the Mountain, a semi-autobiographical novel originally published in 1953. The story follows a young man growing up in Harlem with an abusive, fanatically religious stepfather. There are also subtle references to homosexuality, as well as feeling out of step with the rest of society. The book mirrors much of Baldwin’s own struggles and conflicts within his religious and familial life. Though controversial at the time of its release, the book has been long considered a classic. Time Magazine named it one of the 100 Best English-Language Novels from 1923 to 2005. In 1984, Go Tell It On the Mountain was adapted into a TV movie for ABC, in an attempt to recreate the success of 1977’s Roots.

James Baldwin was an essayist, novelist, playwright, poet, and social critic. His most famous work, amongst many, is Go Tell It On the Mountain, a semi-autobiographical novel originally published in 1953. The story follows a young man growing up in Harlem with an abusive, fanatically religious stepfather. There are also subtle references to homosexuality, as well as feeling out of step with the rest of society. The book mirrors much of Baldwin’s own struggles and conflicts within his religious and familial life. Though controversial at the time of its release, the book has been long considered a classic. Time Magazine named it one of the 100 Best English-Language Novels from 1923 to 2005. In 1984, Go Tell It On the Mountain was adapted into a TV movie for ABC, in an attempt to recreate the success of 1977’s Roots.

James Baldwin was born on August 2, 1924 in Harlem, New York. He grew up poor with his mother and siblings, who had left Baldwin's biological father due to his drug abuse. His stepfather was a preacher and, as Baldwin’s work would suggest, was very strict with the children to say the least. While still a child, Baldwin experienced racially-based harassment from police in his neighborhood. He attended elementary school at P.S. 24, where he wrote the school song. He went to middle school at Frederick Douglass Junior High, where he was influenced by Harlem Renaissance poet Countee Cullen and was encouraged to serve as editor of the school newspaper. Baldwin graduated from DeWitt Clinton High School, where he was the literary editor of the school magazine, but suffered through regular verbal abuse from other students based on his race. He began to have a complicated relationship with religion around the age of 17, due to poor treatment from his stepfather, and his realization of his sexuality. He saw religion as a mirror of black oppression, a theme that would appear many times in his work.

As a young man, Baldwin spent much time in Greenwich Village, and developed long-lasting friendships with painter Beauford Delaney and actor Marlon Brando. By age 24, he had become disillusioned with American racism. He became an expatriate in France, where he would eventually spend most of the latter part of his life. However, Baldwin returned to the U.S. in the summer of 1957. He wrote a number of published essays on the black Civil Rights Movement, toured across America lecturing on activism and socialism, and by 1963 was considered one of the movement’s most prominent spokesmen. He worked closely with Martin Luther King, Jr., and was friends with Langston Hughes, Nina Simone, and Lorraine Hansberry. He and Hansberry, along with Kenneth Clark and Lena Horne, were invited to speak with Robert F. Kennedy to lobby for more civil rights legislation. Baldwin eventually grew distant from the movement; one of the reasons was an outward hostility towards members of the LGBTQ community.

James Baldwin published nearly 20 books over the course of his career. Among the most prominent are Giovanni’s Room (1956), an influential work for its direct narrative on male homosexuality and bisexuality, and Notes of a Native Son (1955), his first collection of essays that were previously published in such magazines as Harper’s, Partisan Review, and The New Leader. He collaborated on other projects, such as A Rap on Race, a transcript of conversations between him and anthropologist Margaret Mead. At the time of his death in 1987, Baldwin was still working on the manuscript for Remember This House, a memoir of his role in the civil rights movement. This manuscript was the inspiration and basis for Raoul Peck's 2016 Oscar-nominated documentary I Am Not Your Negro. Baldwin’s later works have recently seen a resurgence in the zeitgeist for their focus on LGBTQ issues, and overall his writngs have remained a popular part of American literature. The Library of America published a two-volume collection of his works edited by Toni Morrison in 1998, Early Novels & Stories and Collected Essays. The National James Baldwin Literary Society, honoring his legacy, was founded in 1985; a 2005 United States Postal Service stamp bore his likeness; and, on what would’ve been his 90th birthday, the street where he was born (128th Street, between Fifth and Madison Avenues) was named “James Baldwin Place.” Image credit: Portrait of James Baldwin by Lyle Suter, at the Langston Hughes Community Library.